Whether or not to wear a mask has been a confusing message from health organisations and governments, as well as a politicised issue in some countries. The World Health Organisation and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention both recommend wearing face masks (disposable or reusable) along with the other recommended preventative measures and social distancing practices, despite earlier in the pandemic recommending the opposite. This isn’t a failure in science, nor a deliberate attempt to mislead us. It is instead a demonstration of the changing nature of the understanding and knowledge of the SARS-COV2 virus. As more is uncovered by researchers, they update their recommendations and practices, and so should we.

A mixed message

When the ever changing process of science is shown, guts and all, it can present itself in a way that sounds like scientists know nothing and keep changing their minds almost like they are simply guessing. What is instead happening is they are formulating a hypothesis, testing it, analysing it, making recommendations upon those findings, and with every new finding there is a new door to open, a new hypothesis to formulate, and so the cycle begins again. Each time a new hypothesis is supported or unsupported, it may change the recommendations that are given out publicly. With something as virulent, as fast-moving as this pandemic is, scientists are trying to test and report on results as quickly as they can so those hypotheses and those results are changing far more quickly than research into something that isn’t so time-sensitive. Again, this isn’t a failure of science, or even of the reporting method. It is showing us, perhaps in the least pretty and controlled way, how the process happens and that it is the number one priority of these scientists. Scientists didn’t stop researching COVID-19 when they discovered it came from bats and not a lab. Nor did they stop researching COVID-19 when the discovered it lingered on surfaces for up to 48 hours or when they mapped the genome of the virus in March this year. After people recovered from a COVID-19 infection, scientists also didn’t ignore what happened to those people after they tested negative, instead they tracked their progress to understand the long-term impacts of this disease. Each new report you read on a finding related to COVID-19, behind that was a hypothesis, or many, that scientists are desperately trying to find answers to as quickly as possible. With each new report you read the recommendations may change as to how best protect ourselves from this virus, and this is a reflection of learning, of discovery, and of trying to advise us of what is best to do.

A problem of trust

Admittedly, the message has been inconsistent. From the very beginning COVID-19 was seen by many as “just another flu”, and often the seriousness was either underestimated, downplayed perhaps to prevent panic, or in some cases simply (and still) not believed to be a real risk despite the global rising death toll. This lack of a consistent message, the major changes to how we live our lives on a daily basis, the loss of jobs, moral, trust in the people, the governments who are meant to protect us has meant it’s hard to know what to do, what’s necessary, and some people are so over saturated with all this messaging that they can’t help but ignore all of it. This is dangerous. When we can’t trust our leaders to lead, when we look at our scientists and think they are misleading us, when we look at each other with scepticism, we lose control of the situation. The virus doesn’t care what we believe or don’t believe, it’s aim is to spread, to infect as many people as possible and kill those susceptible to it. It doesn’t care about our leaders messages, our neighbours behaviours, it sees nothing but the next vessel to infect, multiply in, and spread from. If we can’t trust our government, our leaders, then we need to look into it ourselves. We need to look to the WHO, to the CDC and see what they are saying, we need to look into the scientific literature and see what the researchers are publishing and if we don’t feel confident in our ability to assess the validity of their claims then we reach out to a friend for help. We need to take it upon ourselves to get educated, and not Facebook meme educated, not viral shared stories educated, but reliable, fact check-able sources and scientific literature to make the best informed decisions.

Learn about your risk

This is what I’ve tried to do. I’ll freely admit that in the very beginning I thought this was just another flu, but very quickly I changed my mind. I started washing my hands and carrying around hand sanitiser. Then I started working from home, and observing the 1.5m distancing rule, and now? Now I am following the research, I am keeping up to date with the recommendations from the WHO and the CDC and I am erring on the side of caution so I wear a mask. Australia may not have the infection rates of the USA or Brazil, but if we keep thinking it won’t happen here, that it’s just a flu, that wearing a mask is over-reacting then perhaps we will become like them. At the very least if we don’t change our behaviour quickly we will be heading into another lock-down and no-one enjoyed that. I think the most important questions to confront yourself with if you are staunchly anti-mask is why won’t you wear a mask, and would you prefer numerous lock-downs as a consequence of not wearing a mask? Really, that’s the choice, wear a mask now and be able to get to work, to go to the shops, to go to the park, to be around other people, OR don’t wear a mask, infection rates soar, and the cycle of lock-downs resume.

A quick look at evidence

A quick search of Google Scholar can find you pages of research articles on the effectiveness of face masks in the prevention of disease transmission. Interestingly, a systematic review of the literature 10 years ago found there to be a substantial gap in the knowledge of the effectiveness of masks to reduce transmission of influenza virus infection. The available evidence at the time did not agree on the use of masks to prevent infection, however since then, with the pressure of the growing pandemic, there has been a jump in research findings.

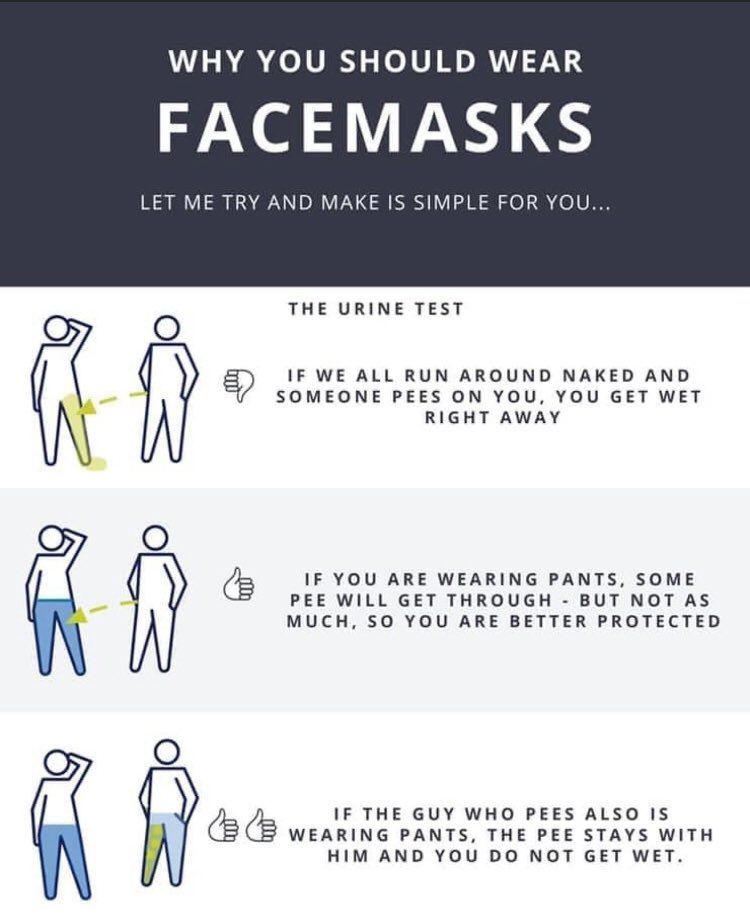

The virus particles of COVID-19 can be spread in the millions in the little respiratory droplets or bits of spit that come out of our mouths as we talk, sing, sneeze, and cough. An experiment using high-speed video footage showed that the hundreds of droplets emitted from the mouth whilst speaking were almost completely blocked when the mouth was covered with a damp cloth. Another study showed that when coughing droplets can travel up to 3.6m (well over our 1.5m distancing rule) but with a mask this distances in reduced to a few centimetres in the best cases (they made note in the paper that some cloth masks work better than others). A very simple demonstration from a virologist in the US really highlights the effectiveness of masks in drastically reducing the amount of respiratory droplets (like those which can spread COVID-19 from infected people) spraying out up to 3.5m in front of you.

These demonstrations, in the controlled settings of the laboratory don’t make up for what has been found in the “real world” during this pandemic. One recent study compared COVID-19 growth rates before and after mask mandates in 16 states across the US which showed a slow in the growth rate of new infections after the masks became mandatory. In Melbourne, Victoria, the state government is introducing mandatory masks for people living in virus “hot spots” clearly because there is enough evidence that masks, along with the other recommended hygiene and distancing practices, reduce the rate of transmission.

In some countries, wearing masks is more acceptable. One study looked at deaths due to COVID-19 across 198 countries and found that those countries were wearing a mask was acceptable, or the government policies favoured mask-wearing had much lower death rates, a comparison of 8% increase in deaths per week in mask supportive countries as compared to a 54% increase in deaths per week in countries without mask support.

More and more small reports are coming out as well showing particular instances suggestive that wearing a mask has prevented transmission of COVID-19 to people in close proximity, when without a mask it would be practically certain they would be infected. A passenger on a flight from China to Canada tested positive for COVID-19 and whilst on the flight had a cough but wore a mask on the plane. The 25 people closest to that passenger all tested negative to the virus despite such prolonged and close contact with someone who was positive. A news report in the Washington Post credits face masks with preventing an outbreak at a hair dressers. Two of the employees were sick with COVID-19 but continued to work whilst wearing face masks. None of the 140 clients they saw contracted the virus despite the close contact, highlighting again the important contribution face masks make to the spread of the virus. Contrast this to the spate of pubs and cafes being closed down across NSW and Victoria recently as hot-spots of infections as popping up.

The best benefit we will get from mask wearing is when the majority of people do it. Modelling work of the pandemic in Washington shows that if 80% of the population adopted mask wearing the death rate could be reduced by between 24-65%, that’s a lot of people who survive simply because we added wearing a piece of fabric across our face.

Whilst there is a vaccine on the way, we could be waiting until sometime next year to have it ready for us. In the mean time we could help curtail this pandemic. We could help more people survive, less people to get infected, the hospitals to cope with the emergencies they get (not only COVID-19 related ones). We could avoid more lock-downs, we could still go out, see friends, travel safely to work, and all we need to do is add wearing a mask in public spaces to our repertoire of pandemic hygiene and social distancing. I don’t think it’s that big of an ask, do you?